Children who are blind lack the functional vision needed to aid in their safe mobility. Two-year-old children who are blind are unable to use hand-held mobility tools to achieve consistent path information (such as white canes), however they are able to walk with a human guide (HG) to achieve orientation and mobility assistance.

HG is a term used to identify when a person who is blind holds onto another person when walking. It is recommended that the guide be positioned a half-step ahead of the person she is guiding. Guiding is a great way to increase speed and direction of travel.

It is very difficult for an uninformed guide (someone who is not a certified O&M specialist) and challenging for informed guides (O&M specialists) to provide effective mobility protection when guiding someone. That means even when guided by the best guide, two-year-old children who are blind do not experience adequate, consistent, or reliable tactile path information.

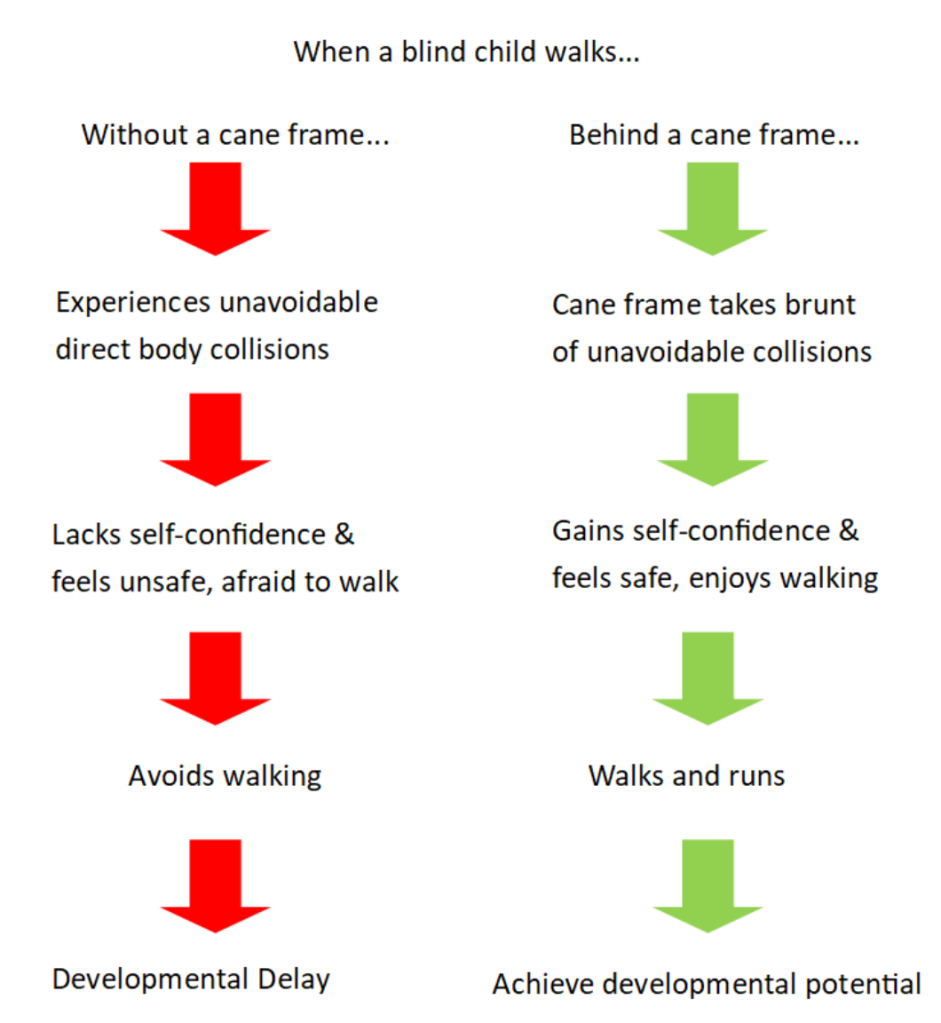

Tactile path information is essential for someone who is blind. They need cane arc safe mobility to assist them in discovering or avoiding obstacles, drop-offs, and surface changes that occur naturally within the environment. A blind toddler walking without reliable tactile path information collide with obstacles even while being guided (see photos below).

It is easier for a guide to walk correctly to a location (provide orientation), than it is for them to provide consistently safe path information (safe mobility) to a person who is blind. It is very challenging for a person acting as a HG to provide safe mobility, because people develop individual path avoidance strategies to achieve personal safe mobility and these individual strategies do not translate well to protecting two people walking together.

Sighted object avoidance strategies rely on sight and are so second nature, that it can be very difficult for sighted guides to remember that a blind person cannot visually avoid obstacles. Toddlers who are blind and encounter collisions when being guided are of great concern, because three-year-old children born blind, with no additional disabilities have been found to be eighteen months behind in gross motor skills (Ambrose-Zaken, 2021).

When children who are blind experience unavoidable collisions when being guided by an adult, it confirms to them that all walking strategies are inherently unsafe, and this fear prevents them from attaining effective guided and self-locomotion strategies. Ambrose-Zaken, Mcallister, & FallahRad (2020) suggested use of the term mobility visual impairment (MVI) to identify those children who require consistent tactile path information. They defined MVI as an inability to visually avoid obstacles. When children with MVI are being guided they may exhibit a tendency to pull away from the guide, have an uneven pace, and collide with obstacles.

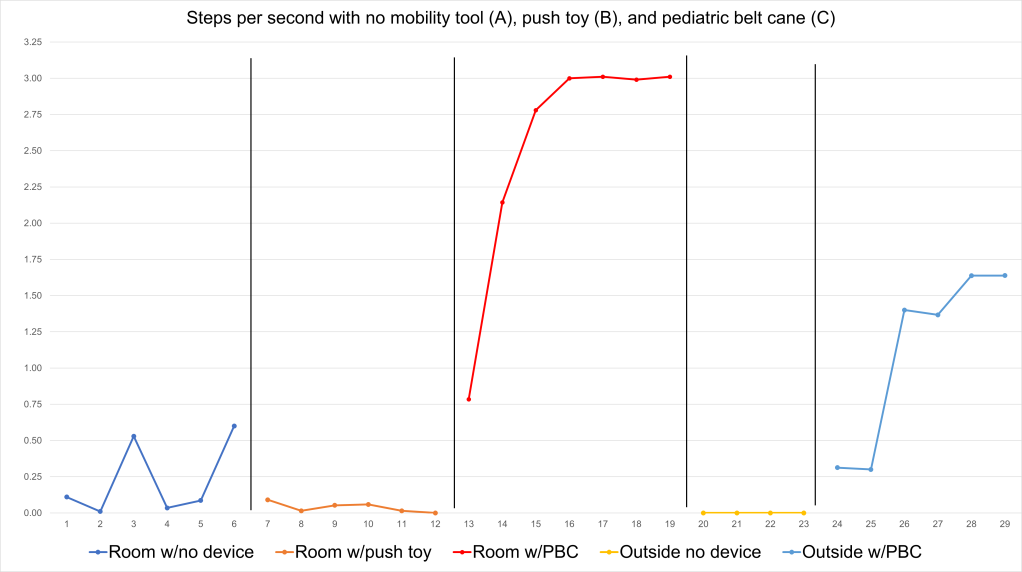

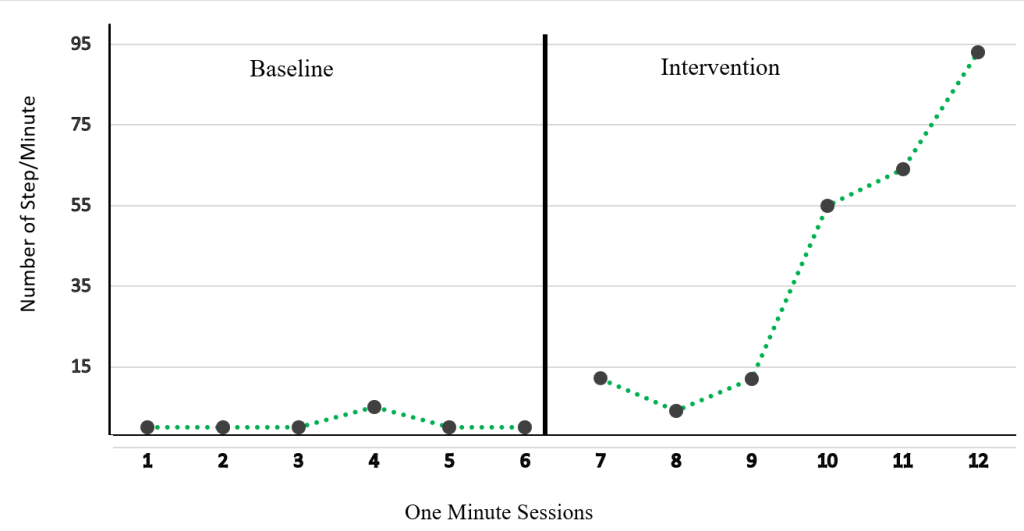

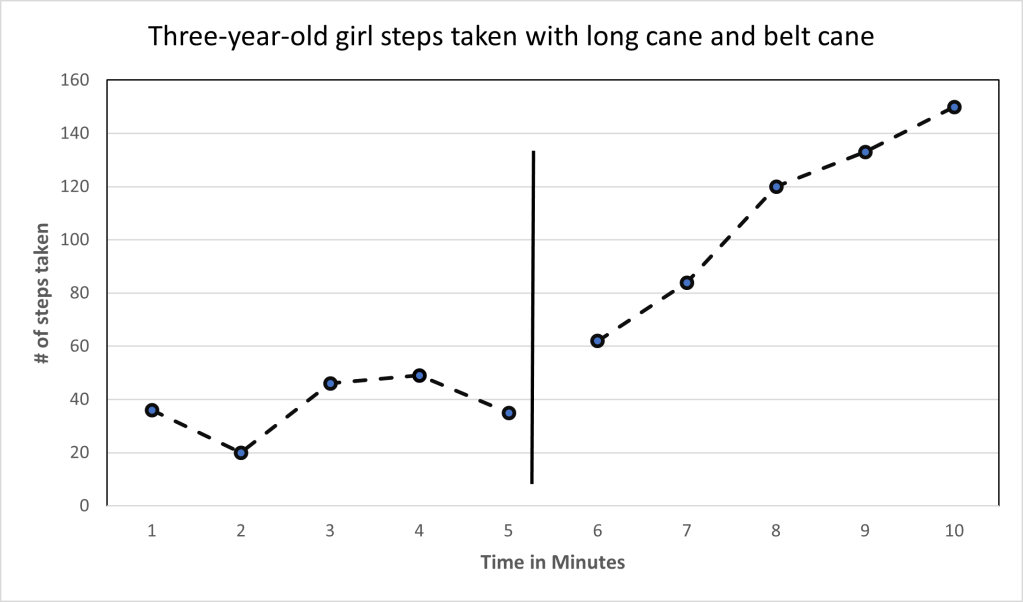

Ambrose-Zaken, FallahRad, Bernstein, Emerson & Bikson (2019) proposed providing children with MVI consistent tactile path information, by having children wear pediatric belt canes (PBCs). The PBC fastens around a child’s waist, and the cane shafts magnetize to the waistband and extend to the floor, two steps ahead of the wearer. The rectangular cane frame moves with the child and provides a two-year-old child who is blind with consistent tactile path information. The purpose of this study was to measure the steps per second taken by a two-year-old boy who was blind walking with a HG before and after obtaining a PBC.

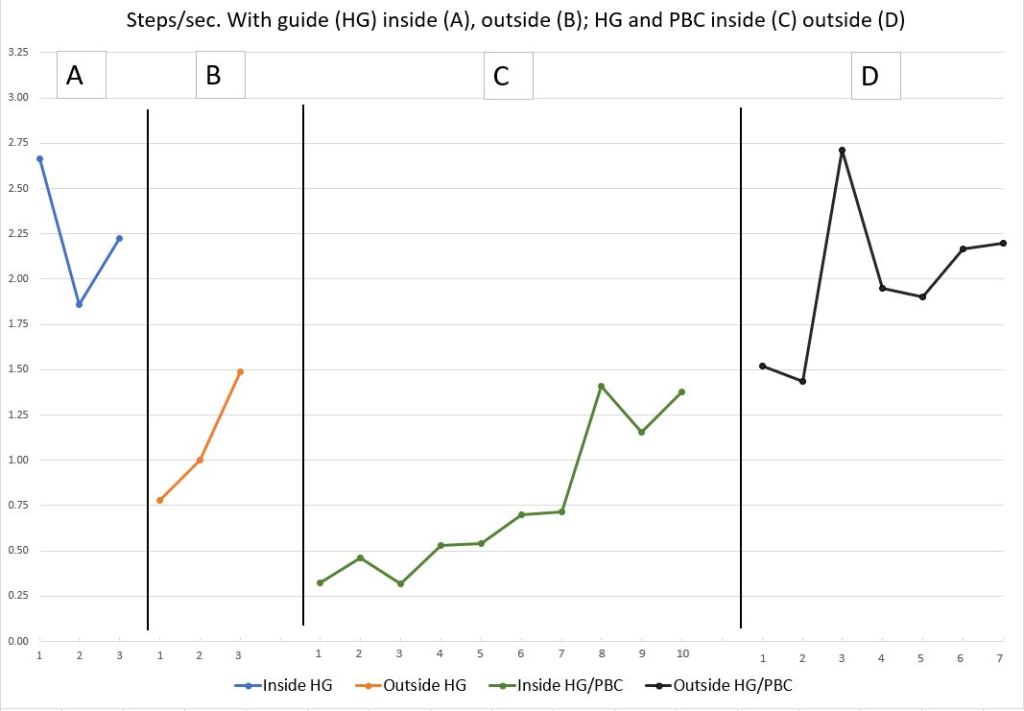

Research design A single-subject repeated measures design research study was conducted with a two-year-old male child who was blind. Baseline data were steps per second walking with a guide at home (A) and outside (B). Treatment consisted of walking with HG wearing a PBC at home (C) and outside (D).

Participant Student M. is a two year old boy with Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis (LCA). He was blind, with no light perception, and was therefore MVI because he was unable to visually navigate any environment safely. His primary mobility tool was HG. Prior to the study, Student M. had not experienced reliable tactile path information when navigating his environment.

Method Twenty-three (23) video segments of Student M. were analyzed. The video segments observed Student M. navigating within his home and outdoors with a human guide before obtaining his belt cane (n=6), and inside his home and outside walking with a HG and wearing his PBC (n=17).

Measurement: Visible steps caught on camera were counted using an iPhone counter app. A step was counted each time he moved a foot forwards or backwards, fast or slow while in contact with a guide. Within videos, a video segment was defined as total time in HG (in contact with a HG until the time when not in contact with the HG). Steps per second was the number of steps taken divided by the time in guide position during that video segment. Within the same video, a new video segment began once the child was asked to stand and/or HG contact resumed. Student M.’s steps occurring when going up or down stairs were not included in the step count or time in guide.

Data and Results Prior to obtaining a PBC, Student M. typically traveled in HG. When walking in guide, his pace consisted of many quick steps. Inside he was observed being guided to specific locations, during one video segment, as he was guided, he was videoed colliding with toys in the family room (see video Human guide poor path detector). Outside he was walking with HG for exercise and fun. In the video of the outside walk with HG he walked in circles (see Matias can’t come when called), you hear his guide ask him if he is “going in circles”.

He walked slower outside in HG, than inside in HG. Video of intervention “C”, showed Student M.’s steps per second after putting his PBC on the first time, at home. Wearing the cane inside for the first time, Student M. took very few steps in HG because during the first seven and a half minutes of the video, he was crying and appeared to resist wearing the PBC. Overtime, wearing his PBC inside he walked much slower steps per second compared to when walking with a HG without a PBC at home. When wearing the PBC outside, he walked much faster than walking outside in HG only. Outside, wearing the PBC, his steps were longer, more even, and his pace and path direction matched his guide’s pace and path direction. The length of the routes walked with the PBC were longer than those walked in HG only. The outside steps per second when wearing the PBC were about the same as steps per second walking inside with HG and no PBC.

Discussion

The data of Student M.’s steps per second suggested that the introduction of a PBC reduced the number of steps he took when walking with a guide. When he put the PBC on the first time, his steps per second were less frequent because, although in guide position, he was crying and resisting the PBC and resisted walking. Overtime, Student M.’s walking quality improved in HG wearing his PBC.

When Student M. was outside wearing his PBC he walked a straighter path, longer strides, and a more even pace (see Matias Guided at the Zoo). The steps per second measurement demonstrated that Student M. initially resisted walking when wearing his cane when he was first introduced to it in phase “C”. However, his steps per second increased overtime when he was no longer crying or resistant to wearing his PBC. When walking HG only, his quick steps were at odds with the pace of his guide.

His walking speed with HG and wearing his PBC was more closely matched to his guide’s pace. After initially rejecting his PBC, Student M. accepted wearing his cane after eight minutes and was able to enjoy the benefits of independent path information simultaneously to achieving the advantage of walking with an adult guide. His gait and path improved, suggesting that the measure of steps per second may not be a sensitive enough measurement when examining the benefits of consistent path information for two-year-old boys who are blind.

It is important to replicate this study to see whether these findings are consistent across subjects. Student M.’s response to wearing the PBC initially was tearful and resistant, however after those first seven minutes of tears, his response to wearing the PBC improved. This suggests that the advantages of wearing the PBC should not be withheld from two-year-old children, if they cry at first attempt.

Two-year-old boys may only be upset for a few minutes after first introduction to the cane, and afterwards begin to obtain real benefit from walking with consistent accessible path information. It is important to replicate this study to learn whether other two-year-old blind toddlers who cry when first introduced to wearing PBCs, also improve their mood, gait and pace given sufficient time, experience and distractions. It is often true for very young learners, they need sufficient time before they begin to trust the tactile path information benefits they receive when wearing a PBC.

Photos of collisions with a HG with and without PBC

References

Ambrose-Zaken, G.V. (2021, March 25-27). Importance of Safe Mobility to Achieving Developmental Milestones: Part 1. [Conference presentation]. Virtual 2021 Rocky Mountain Early Childhood Conference. United States.

Ambrose-Zaken, G., McAllister, J., & FallahRad, M. (2020). Mobility Visual Impairment and Blindness: A New Term to Identify a Major Contributor to Developmental Delays in Children. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Ambrose-Zaken, G. V., Fallahrad, M., Bernstein, H., Wall Emerson, R., & Bikson, M. (2019). Wearable Cane and App System for Improving Mobility in Toddlers/Pre-schoolers With Visual Impairment. Frontiers in Education, 1(4), 1-13.